By Michael Hogan, Executive Convenor, Thriving Qld Kids Partnership

Toward productivity for purpose: System approaches to building human capital, from the beginning

As the Government commences it’s second term, the Prime Minister and Treasurer have opened the door for a public policy reset on productivity. The Treasurer said in his National Press Club address on 18 June 2025: “… lifting productivity is about empowering workers and making the most of our human capital”. He added that: “We’ve encouraged a broader approach to productivity that goes beyond the old, tired and formulaic fights.”

ARACY, the auspice for the Thriving Queensland Kids Partnership, is making the case for a new paradigm of what productivity means – what it looks like, how we measure and value it. ARACY is urging the Treasurer’s Economic Reform Roundtable to take this opportunity not to reform productivity, but to redefine it.

We need a new paradigm of productivity, fit for a modern care and knowledge economy, that drives a fairer future instead of mortgaging the next generation. We need what Centre for Policy Development calls productivity with purpose – productivity as a tool to build an equitable, inclusive, and sustainable society.[i]

ARACY’s key points are a call for:

- Intergenerational fairness: economic reform must look beyond old levers and paradigms unsuited to a care and knowledge economy if we want to build a sustainable, fair, and prosperous future for all generations.

- More than business or the private sector: the care and social sectors also need to reconsider current ways of working that create friction, hinder innovation and efficiency, and hold current conditions in place.

- Smarter investment: investing early in child, family and community wellbeing – including by reducing friction in the systems that serve them – reduces longer term costs in health, justice, and welfare, and boosts prosperity and fairness for all Australia.

- Cross-sector prioritisation: the wellbeing of children, families and communities isn’t just a social issue – it’s economic policy, health policy, education policy, and productivity policy[ii].

Here we delve deeper into one aspect of that broad agenda – a systems approach to human capital development, from the beginning, i.e. from pregnancy.

Our contention is that it’s time to take a broader and deeper view, and set a much more ambitious agenda on the formation of the skills and capabilities – cognitive and non-cognitive – and the human agency and human connectivity – that are the essence of ‘human capital’.

Rightly, the Albanese Government points to significant achievements and foundations laid in the first term:

- reform of industrial relations

- funding of free TAFE

- the formation of Jobs and Skills Australia, including the HumanAbility Council

- measures for women’s economic participation and equity

- advances in more equitable and sustainable schools funding toward Gonski 2.0

- steps and commitments to universal early childhood education and care

- investments and reforms in other so-called ‘care economies’ such as disability, aged care, mental health.

However, there is another horizon of reform that is required for a transformative reset on productivity, sustainability and resilience i.e. a more purposeful and systemic approach to building human capital.

This involves a fundamental but doable design shift to existing policies, investments and services. It accords with the Treasurer’s requirement to not require an additional huge stream of investment. Indeed, it offers a way to better use existing resources, and to avoid both costly responses to harms done and less effective investments in remediation. It is also a change that can serve the Albanese Government’s stated goal of greater ‘intergenerational equity’.

For all the mentions of ‘human capital’, often in passing, in official reports on productivity over the past few decades, there has been precious little attention to the actual human nature and mechanics or ‘technologies’ of skills acquisition across the life course.

The usual focus of concern in productivity debates is on cognitive skills or technical skills, and on re-skilling for the ‘knowledge economy’. Increasing attention is emerging on social skills and, now, on the likely impacts of generative and determinative AI (artificial intelligence).

As James Heckman, the Nobel prize-winning US economist of early childhood development, has been telling the world for over 20 years, this is too narrow, too little and too late.

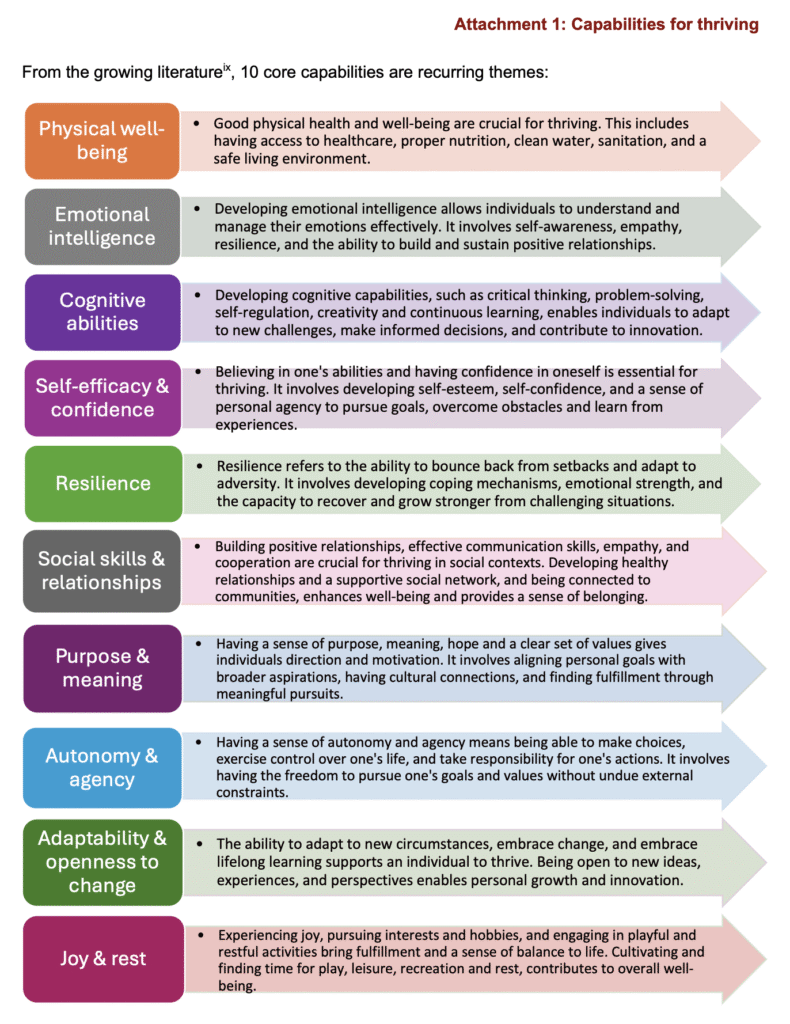

Human development encompasses all aspects of growth and progress, through the ups and downs of life, including physical, cognitive, emotional, and social dimensions. All of these are brain-related. The vast literature on human development and capabilities, available via good search engines and AI, give us ready access to various schemas of human capital and capability (see for example Attachment 1). This again is not such a ‘knowing problem as a doing one’.

A succinct description of brain-based ‘core capabilities’ is provided by the Harvard Center on the Developing Child (HCDC) state[iii]:

“Mounting research from neuroscience and psychology tells us that there is a set of underlying core capabilities that people use to manage life, work, and parenting effectively. These include, but are not limited to: planning, focus, self-control, awareness, and flexibility. To scientists, these capabilities fall under the umbrella of self-regulation and executive function.”

As the saying goes, ‘who and what surrounds us, and what happens to us, shapes us’. Our capabilities are shaped by our genes, relationships, experiences, cultures and all the environments and systems impacting our development. They can be impaired by adverse experiences and interactions in childhood, and indeed, by the experiences of our parents and caregivers, and by their caregivers, and so on.

As we know, building these capabilities start from pre-pregnancy and conception, and continues through pregnancy, infancy, childhood, adolescence and across the life course. We also know that adversity profoundly affects our brains and bodies, with lifelong health and wellbeing consequences, including on our core capabilities.

As the HCDC states:

“Chaotic, stressful, and/or threatening situations can derail anyone, yet individuals who experience a pile-up of adversity are often even less able to deploy all of the skills they have to cope with challenging circumstances. Early in life, the experience of severe, frequent stress directs the focus of brain development toward building the capacity for rapid response to threat and away from planning and impulse control. In adulthood, significant and continuous adversity can overload the ability to use existing capacities that are needed the most to overcome challenges.”

These capabilities support individuals to reach their full potential and lead fulfilling lives. Importantly, these core capabilities work in synergy – they are interconnected and mutually reinforcing. They are also each a continuum, adjusting through life’s ups and downs and as we relate and interact with others.

As Heckman says, ‘skills beget skills in compounding and dynamic ways’. Collectively they contribute to creating a society that promotes wellbeing, equality, and sustainable progress for all.

Nurturing these capabilities positively is a role and responsibility for all. It requires support for our caregivers, and the collective effort of all systems and organisational leaders, policy makers, program managers and practitioners[iv].

Despite decades of science and evidence, no Australian jurisdiction – Federal or State and Territory – yet has a comprehensive framework or strategy for ‘human capital development’.

Astonishingly, we don’t have a shared public statement about the capabilities people require for a good, productive and resilient life – a life that they and our community values.

Nor has any Australian jurisdiction done the hard yards in and across our many ‘human development’ systems of doggedly translating and deeply embedding that science and evidence. It is hard to find it explicit in policy intent and implementation via strategies, national partnership agreements, program and investment specifications, service design, quality standards or the pre- and in-service skilling of workforces.

Every portfolio has a direct or indirect impact of human capital, yet very little planning or accounting is done (with the exception of education and transition to work initiatives, and to some extent in disability) for how they contribute to, or harm, the acquisition of life skills.

Given the way we organise government portfolios and departments – health, education, employment etc. – there is no one Minister or agency responsible for human capital or human development, and there are few metrics deployed at a whole-of-government or agency level.

Of course, to ‘make the most of human capital’ as the Treasurer wants, we ‘have to build it’, and definitely not deplete it.

Skills acquisition starts and keeps happening from birth in families and homes, and in playgrounds and libraries, well before early childhood education and care (ECEC) and schools. It continues happening as children and young people navigate all the environments and the systems (not just schools) that shape their brains and bodies, and all the formative relationships and experiences that shape their lives. Heckman and co have evidenced that the crucible of skills formation is what happens in families, especially in the early years.[v] It is not just the job of ECEC, schools, TAFEs, Registered Training Organisations (RTOs), universities or employers to build skills.

At least in education systems, there is growing attention to the potential dividends of purposeful effort to build cognitive, social and emotional skills. For example, the recent report from Learning Creates Australia, The economics of more capable young people: improving young people’s social and emotional skills for learning, states that[vi]:

“New economic modelling reveals that improving social and emotional skills across the school-age population could generate at least $22 billion in long-term value through enhanced earnings, productivity mental health and workforce participation. This is intentionally conservative modelling. … The true value extends far beyond these numbers to include lower welfare costs, reduced crime, social cohesion, civic engagement, and national resilience. … The future economy demands team players, resilient problem solvers and ethical collaborators. Investing in these capabilities is no longer optional – it’s a strategic imperative for national prosperity and generational wellbeing”.

So, what about other ‘human’ systems of parenting and family support, child health and development, child protection, mental health, juvenile and adult justice, disability and so on?

Over the past few decades, we’ve got used to referring to human services or community services systems, and more recently, to care economies. We focus understandably on the quantity, cost and efficiency of ‘service’ delivered. Thankfully we now see emerging a much stronger focus on the critical ‘relationality’ of these services[vii].

However, apart from a critique of the ‘dependency’ that care services and interventions can create, we are yet to see such a systematic focus on the ‘productivity’ of these services in terms of the skills and mindsets, and the agentic and resilient traits and behaviours, they should ‘produce’.

The Albanese Government has agreed on ‘a 5-pillar productivity agenda with National Cabinet’:

1. Creating a more dynamic and resilient economy.

2. Investing in the net zero transformation.

3. Building a skilled and adaptable workforce.

4. Harnessing data and digital technology.

5. Delivering quality care more efficiently.

Human capital or human development is implicit, but in the broadest and deepest sense, risks being hidden. It is also of civic, social and environmental importance, not just economic. It is vital for sustainable development.

As the Treasurer said: ‘Of the six biggest structural pressures on the Budget, four are care‑related: Health, the NDIS, aged care, and early childhood education and care.’

We can’t afford not to be focused and purposeful about the human capital dividend of each and every one of these systems and their day-to-day interactions with citizens and consumers.

What if every ‘human system’ was explicit in its intent and accounting for building human capital? What if we pursued not just universal ECEC, but a universal early childhood development eco-system, equitably resourced and well adapted to the context and needs of every child, in every family, in every community.

What if we recast ‘child protection systems’ that focus on reducing harms and risks in the here and now, into integrated ‘child development and wellbeing systems’ that apply the fundamental principles enunciated and evolved by the Harvard Centre on the Developing Child over the past decade? Those principles are:

– reduce significant adversities and toxic stress

– build positive relationships and supports

– build capabilities

– recognise the uniqueness of each child in their family and community contexts, and

– create healthy and enabling systems and environments.

These are principles and approaches that underpin what most parents endeavour to do for their children.

There are approaches to child development and family wellbeing based on these principles that are being deployed elsewhere. In Alberta, Canada – the Alberta Family Wellness Initiative is 10 years into a systematic whole-of-jurisdiction approach with commitment to development, resilience and wellbeing at the individual, family, neighbourhood, organisation and systems levels[viii]. They have systematically deployed what we know from neuroscience and related fields, using the Brain Story and The Resilience Scale, as ways to build and use common understanding, language, skills, tools and methods that support people to deal with adversity and to thrive.

When we neglect to explicitly factor in and account for the development of the full suite and core capabilities and connections, at best we constrain their development and at worst we do harm that can last a lifetime. That is a drag on productivity. It is also:

– a waste of human potential

– an unnecessary cost for our society and economy

– a reason we perpetuate fragility and intergenerational adversity and inequity.

To transcend and transform, we need a new paradigm of ‘human development eco-systems’. All of our systems and services must be redesigned to purposefully build core skills and connections.

Just consider what we spend on responding to the consequences – the costs of systems dealing with ‘human-induced’ physical and mental ill-health, chronic disease and disorders, crime, child protection, domestic and family violence, and under-employment. All of these are associated with early adversity and under-investment in both prevention and development.

So how might we be more purposeful and accountable for human capital production?

Here are 11 actionable, practical and cost-effective propositions:

- Reframe ‘the last pillar’ of the proposed Productivity Agenda to ‘delivering quality care, learning and justice systems more efficiently, developmentally and equitably’.

- Broaden the commitment to universal ECEC to universal, proportionate and localised early child development eco-systems, and extend that progressively to the middle years and adolescence.

- Develop whole of jurisdiction ‘human capital’ frameworks focused on development, wellbeing and resilience across life stages.

- Replicate the collaboratives on ‘brain capital’ – across the life course – happening in North America and Europe, Africa and South America, including through bodies such as the OECD, the World Economic Forum, and the annual UN Science Summit.

- Recommit to action at national, state and local levels on the Sustainable Development Goals, which have human dignity, inter-dependency, capability and agency at their core.

- Write ‘human development’ goals and measures into every human system strategy, national partnership agreement, investment logic, program specification, service design, practice guide and quality standards.

- Act on the call from Learning Creates Australia to ‘transform Australia’s complex educational landscape’ to ‘value not just what students know, but who they are becoming’.

- Strip back antiquated risk, regulatory and anti-collaborative frameworks and program boundaries, and rationalise and re-engineer programs, that get in the way of holistic, quality, relational and developmental interventions.

- Reorient existing (and new) investments in child, family and community services and place-based initiatives to reduce adversities, strengthen positive relationships and build capabilities, contextualised for place and culture, and redistributed equitably and proportionate to need.

- Rewrite curricula and training for every ‘human’ development role to build the core, common and contemporary knowledge, language, skills and tools of every practitioner and educator, manager and leader, and build this into the ‘DNA’ of our systems, services and practices.

- Invest in the community, service and systems leaders, change agents and brokers that are building and weaving together developmental systems and environments at all levels.

As the Treasurer concluded in his recent Press Club address:

‘But the stakes are too high in our economy – the opportunity is too substantial – to waste this term or waste our time.’

Let’s add: ‘or to waste human potential’.

Michael Hogan, Executive Convenor, Thriving Qld Kids Partnership

www.tqkp.org.au

[i], v Centre for Policy Development (2025) Productivity with Purpose: Clear pathways to a more equitable future, CPD discussion paper.

[ii] https://www.aracy.org.au/news/dont-just-reform-productivity-redefine-it/

[iii]i See: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/science/deep-dives/adult-capabilities/

[iv] See Rubenstein, L. (2021), Building Children’s Potential: A Capability Investment Strategy, ARACY Policy Brief (see https://www.aracy.org.au/documents/item/667).

[v] See www.heckmanequation.org

[vi] Learning Creates Australia & Impact Economics and Policy. (2025). The economics of more capable young people: improving young people’s social and emotional skills for learning

[vii] See, for example, www.centreforrelationalcare.org.au

[viii] See www.albertafamilywellness.org